All Eyes on View

Jan 2nd, 2013 @ 01:55 am › Steven Heller

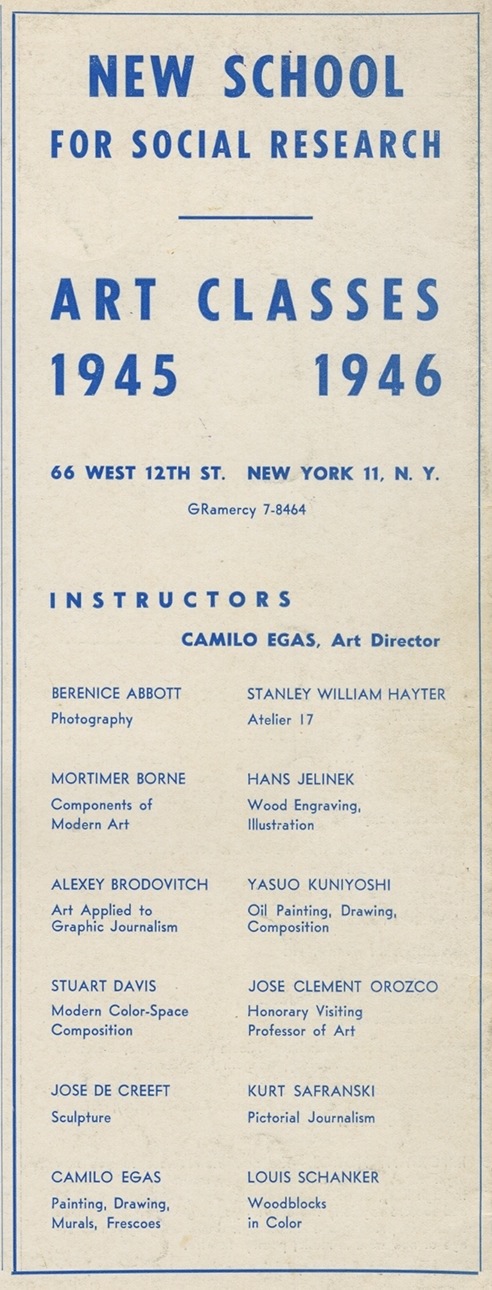

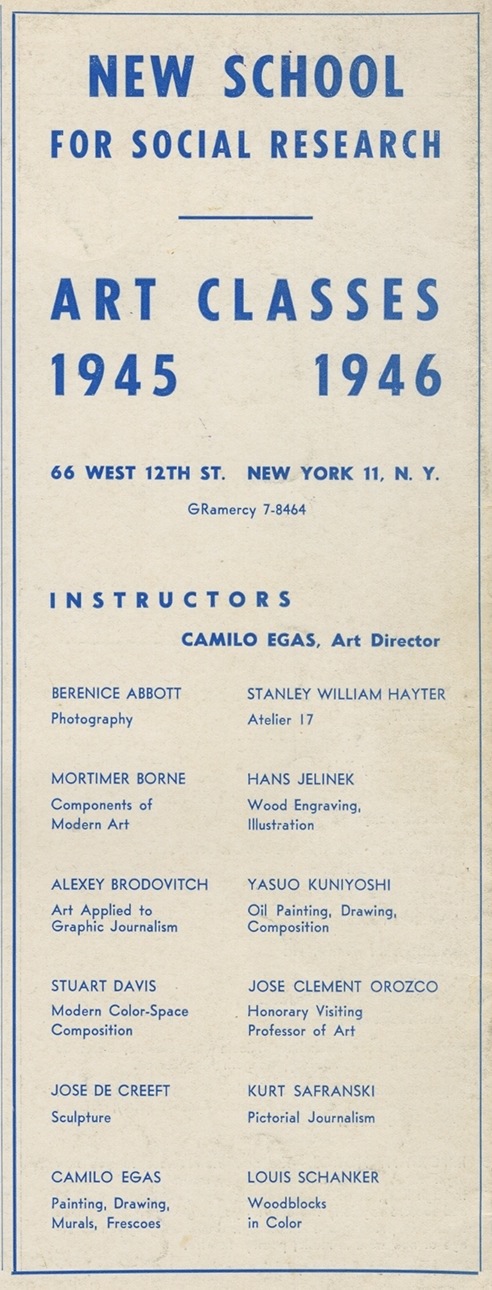

You may have seen View magazine before. It is not one of the forgotten ones. It is a legendary one that is always interesting to revisit. It was edited by John Henri Ford, a surrealist poet from Mississippi. View included writing and art by Paul Bowles, Philip Lamantia, Harold Rosenberg, Aaron Copland, and Marcel Duchamp, among others. The issue below with Duchamp’s cover is devoted to the artist who designed the collage pages inside. The Morris Hirshfield primitive covers an issue on “The Macabre.” And look at the advertisement below for The New School art classes—some great teachers made the grade.

The following text is excerpted from my book Merz to Emigre and Beyond: Avant Garde Magazine Design of the Twentieth Century:

View: Through the Eyes of Poet’s New York’s first Surrealist journal appeared in September 1940 as a six-page tabloid. Edited by poet Charles Henri Ford, the former American editor for the London Bulletin, the British surrealist revue published by the London Gallery between 1938 and 1940, View’s mission for its seven year duration (36 numbers in 32 issues) was to fill the void of European avant garde periodicals that ceased with the war. Ford positioned his publication between the “little magazine” transition (the vanguard journal edited in Paris by Eugene Jolas and Elliot Paul between 1927 and 1938) and Minotaure. After View’s 1941 “Surrealist issue” edited by Nicolas Calas it became the most important American surrealist publication, featuring text and visual contributions from all the principles in the circle.

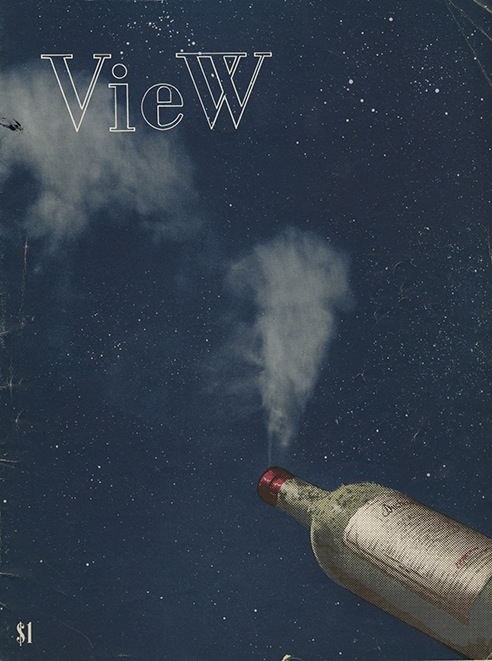

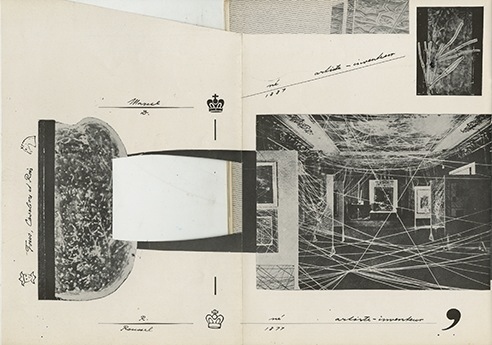

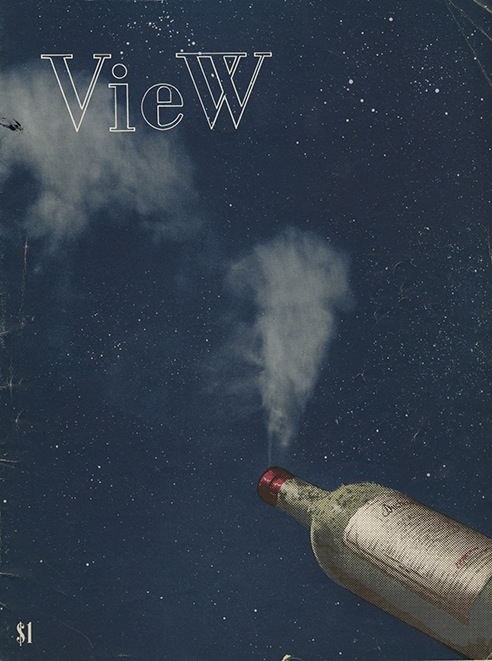

By 1943 View shifted from the tabloid to a more standard magazine format printed on slick paper with full color covers and the occasional gatefold. This increased the financial burden of production that the maximum 3000 paid circulation did not cover, so to maintain a regular quarterly publishing schedule Ford accepted relatively expensive advertisements for fashions and perfumes, among those already for books, periodicals, and other cultural events. Associate editor, Parker Tyler was in charge of View’s typography and graphic design and produced a highly sophisticated graphic persona on a par with Minotaure and yet unique to View. The covers created by Surrealist standard bearers, Andre Masson, Man Ray, Kurt Seligmann, and Marcel Duchamp, as well as other modern artists, Alexander Calder, Fernand Léger, and Georgia O’Keeffe, were the most adventuresome of any American magazine. Moreover, these were not paintings arbitrarily placed on the covers but images designed especially for this venue. Occasionally, the common View masthead (set in a Bodoni typeface) was designed by the cover artist: Isamu Noguchi’s 1946 cover is a superb example of this transformation: Here the letters of View are sculptural elements reading diagonally down the page and bracketing the sculpture is the centerpiece of the cover.

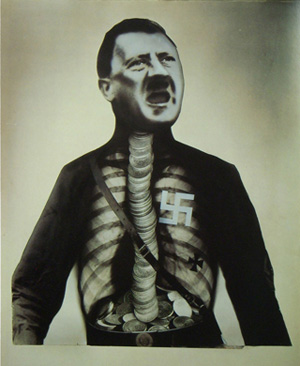

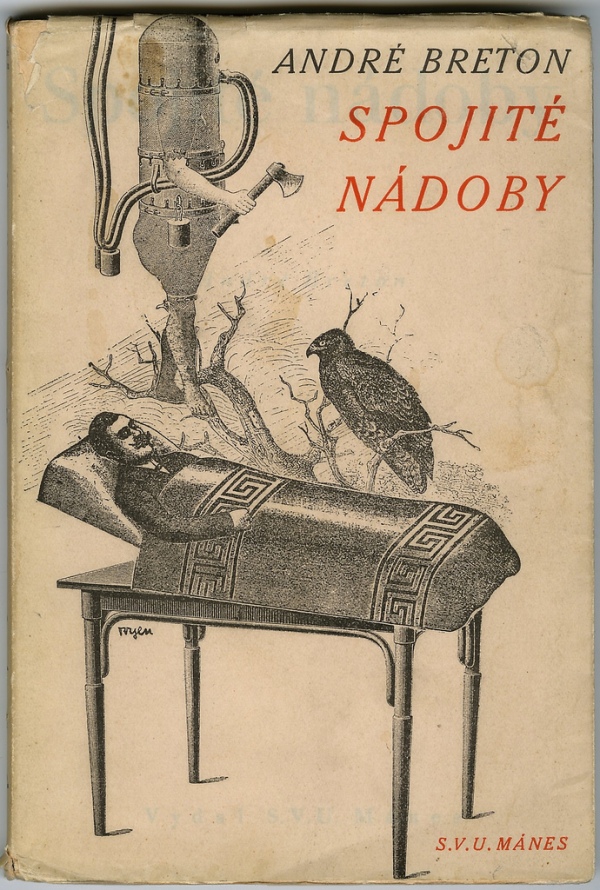

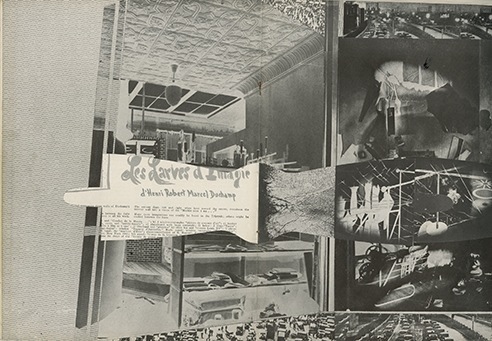

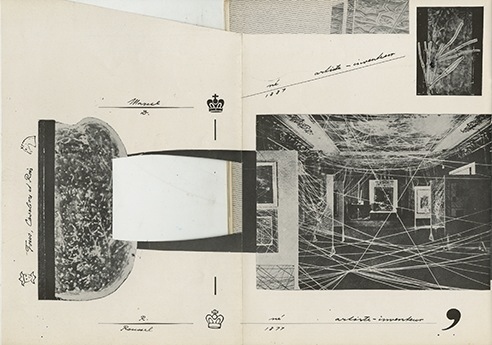

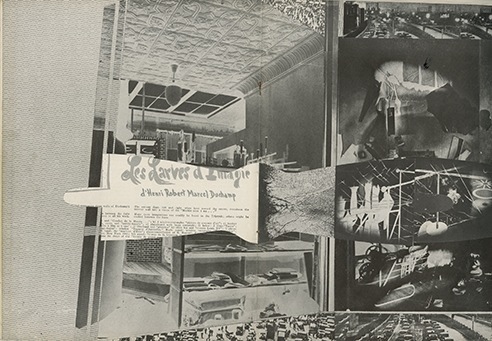

View covered the Dada experience and introduced the key surrealists to New York. Andre Breton’s first American interview was published here. An entire issue (1942) was devoted to Max Ernst with article on him by Breton; and a spectacular issue (1945) featured Duchamp, complete with layouts designed by the artist — this being the first monograph ever published of his work. An essay by Peter Lindamood describes the technical machinations involved in, and thereby demystifies, the creation of Duchamp’s View cover, a montage of a smoking wine bottle. He explained how this master of “art-plumbing expediency” rigged up a smoke pipe under the bottle and then manipulated the various halftone layers to achieve the desired effect. In this and other articles View gave Surrealist art a human context that was curiously absent in the pseudo-scientific and hyper analytic writing found in the earlier European journals.

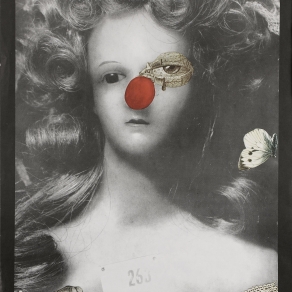

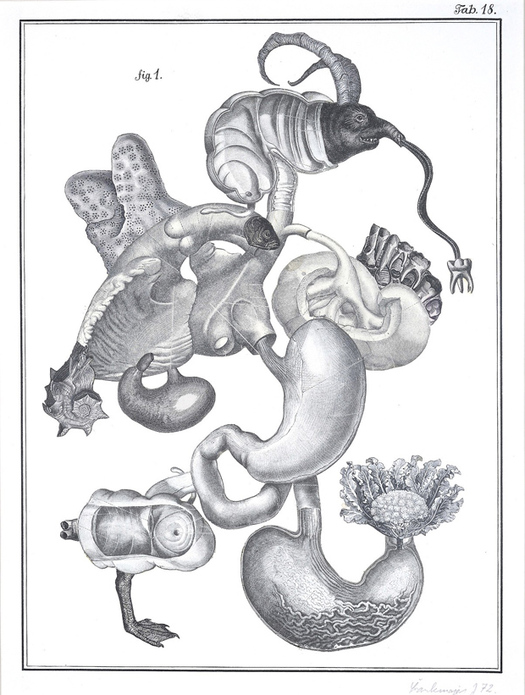

Coverage of the European vanguard was only a part of the editorial menu. Ford felt a duty to bridge the transatlantic gap by bringing Americans into the Surrealist fold and in 1943 View was the first to publish Joseph Cornell’s earliest “found art” compositions (“The Crystal Cage: Portrait of Berenice”). It gave outlet to the emerging American vanguard writers and artist-writers, including Henry Miller, Marianne Moore, William Carlos Williams, Alexander Calder, and others. But Ford also published the naïve and self-taught Surrealists, notably the African-American artist Paul Childs. Morris Hirshfield, whose beguilingly detailed and folk paintings were discovered by Sidney Janis in the thirties, was also part of the View community. Hirshfield’s 1945 cover intricately rendered cover of a cleverly veiled nude was surrealism at its most slyly innocent.

View celebrated the artist as visionary and Surrealism as a wellspring of artistic eccentricity. In its role as avant garde seer the magazine overstepped the bounds of propriety, and therefore in 1944 was banned by the U.S. Postal Service presumably for publishing nudes by Picasso and Michelangelo. However, despite its confrontational stance and the debates about Marxism, Communism, and Trotskyism that were carried on in European Surrealist circles, View did not advocate ideological political activity, but rather supported the right of individual artistic freedom – and eclecticism. “View’s editors thought it delusional to believe that art could ever serve any cause other than its own,” wrote Catrina Neiman in View: Parade of the Avant-Garde (Thunder Mouth Press, New York, 1991), who further notes while certain poets of the day urged opposition to the inevitable world war, “View printed no editorials denouncing the war.” Though it did maintain a pacifist stance that supported conscientious objection.

View caused its share of acrimony among the skirmishing groups who sought dominance for their respective art forms. Surrealism was not universally admired, and The Partisan Review, a left-leaning intellectual journal, declared that Surrealism was both decadent and dead, endorsed abstract art as the new avant garde art. This was no mere preferential disagreement but a contest for what genre and which artists would dominate the museums, galleries, and private collections. View tried to preserve Surrealism’s importance and so ignored competing arts. Yet this advocacy was not so much militancy over an ideological cause, but a campaign for the hegemony of style.

View was a significant outlet for Surrealism it was also uncommitted to the movement as a “party,” and thus became an instrument for popularizing the avant garde. Surrealism as a style was, no pun intended, ready-made as an advertising trope. “Ford did not disdain commercial avenues of support,” states Catrina Neiman, “…on the contrary, he knew not only how to navigate capitalism but hoe to appreciate (appropriate) its imagery, namely through the lens of camp, a ‘view’ that converged with surrealism then and with Pop Art twenty years later.” Despite the paid advertising, however, View ceased publishing in 1949.

For more Steven Heller, check out The Education of an Art Director—one of the many Heller titles available at MyDesignShop.com.

Categories: Daily Heller, Steven Heller

Tags: Daily Heller, Steven Heller, View magazine

Read more: All Eyes on View | Imprint-The Online Community for Graphic Designers

///